Azimuthal quantum number

The azimuthal quantum number is a quantum number for an atomic orbital that determines its orbital angular momentum and describes the shape of the orbital. The azimuthal quantum number is the second of a set of quantum numbers which describe the unique quantum state of an electron (the others being the principal quantum number, following spectroscopic notation, the magnetic quantum number, and the spin quantum number). It is also known as the orbital angular momentum quantum number or second quantum number, and is symbolized as ℓ (lower-case L).

Contents |

Derivation

Associated with the energy states of the electrons of an atom is a set of four quantum numbers: n, ℓ, mℓ, and ms. These specify the complete and unique quantum state of a single electron in an atom, and make up its wavefunction or orbital. The wavefunction of the Schrödinger wave equation reduces to three equations that when solved, lead to the first three quantum numbers. Therefore, the equations for the first three quantum numbers are all interrelated. The azimuthal quantum number arose in the solution of the polar part of the wave equation as shown below. To aid understanding of this concept of the azimuth, it may also prove helpful to review spherical coordinate systems, and/or other alternative mathematical coordinate systems besides the cartesian coordinate system. Generally, the spherical coordinate system works best with spherical models, the cylindrical system with cylinders, the cartesian with general volumes, etc.

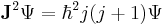

An atomic electron's angular momentum, L, is related to its quantum number ℓ by the following equation:

where ħ is the reduced Planck's constant, L2 is the orbital angular momentum operator and  is the wavefunction of the electron. While many introductory textbooks on quantum mechanics will refer to L by itself, L has no real meaning except in its use as the angular momentum operator. When referring to angular momentum, it is best to simply use the quantum number ℓ.

is the wavefunction of the electron. While many introductory textbooks on quantum mechanics will refer to L by itself, L has no real meaning except in its use as the angular momentum operator. When referring to angular momentum, it is best to simply use the quantum number ℓ.

The energy of any wave is the frequency multiplied by Planck's constant. This causes the wave to display particle-like packets of energy called quanta. To show each of the quantum numbers in the quantum state, the formulae for each quantum number include Planck's reduced constant which only allows particular or discrete or quantized energy levels.

This behavior manifests itself as the "shape" of the orbital.

Atomic orbitals have distinctive shapes denoted by letters. In the illustration, the letters s, p, and d describe the shape of the atomic orbital.

Their wavefunctions take the form of spherical harmonics, and so are described by Legendre polynomials. The various orbitals relating to different values of ℓ are sometimes called sub-shells, and (mainly for historical reasons) are referred to by letters, as follows:

| ℓ | Letter | Max electrons | Shape | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | s | 2 | sphere | sharp |

| 1 | p | 6 | two dumbbells | principal |

| 2 | d | 10 | four dumbbells or unique shape one | diffuse |

| 3 | f | 14 | eight dumbbells or unique shape two | fundamental |

| 4 | g | 18 | ||

| 5 | h | 22 | ||

| 6 | i | 26 |

A mnemonic for the order of the "sub-shells" is some poor dumb fool. Another mnemonic for the order of the "sub-shells" is silly professors dance funny. The letters after the f sub-shell just follow f in alphabetical order.

Each of the different angular momentum states can take 2(2ℓ + 1) electrons. This is because the third quantum number mℓ (which can be thought of loosely as the quantized projection of the angular momentum vector on the z-axis) runs from −ℓ to ℓ in integer units, and so there are 2ℓ + 1 possible states. Each distinct n,ℓ,mℓ orbital can be occupied by two electrons with opposing spins (given by the quantum number ms), giving 2(2ℓ + 1) electrons overall. Orbitals with higher ℓ than given in the table are perfectly permissible, but these values cover all atoms so far discovered.

For a given value of the principal quantum number n, the possible values of ℓ range from 0 to n − 1; therefore, the n = 1 shell only possesses an s subshell and can only take 2 electrons, the n = 2 shell possesses an s and a p subshell and can take 8 electrons overall, the n = 3 shell possesses s, p and d subshells and has a maximum of 18 electrons, and so on. Generally speaking, the maximum number of electrons in the nth energy level is 2n2.

The angular momentum quantum number, ℓ, governs the number of planar nodes going through the nucleus. A planar node can be described in an electromagnetic wave as the midpoint between crest and trough, which has zero magnitude. In an s orbital, no nodes go through the nucleus, therefore the corresponding azimuthal quantum number ℓ takes the value of 0. In a p orbital, one node traverses the nucleus and therefore ℓ has the value of 1. L has the value ħ.

Depending on the value of n, there is an angular momentum quantum number ℓ and the following series. The wavelengths listed are for a hydrogen atom:

- n = 1, L = 0, Lyman series (ultraviolet)

- n = 2, L = √2ħ, Balmer series (visible)

- n = 3, L = √6ħ, Ritz-Paschen series (short wave infrared)

- n = 5, L = 2√5ħ, Pfund series (long wave infrared).

Addition of quantized angular momenta

Given a quantized total angular momentum  which is the sum of two individual quantized angular momenta

which is the sum of two individual quantized angular momenta  and

and  ,

,

the quantum number  associated with its magnitude can range from

associated with its magnitude can range from  to

to  in integer steps where

in integer steps where  and

and  are quantum numbers corresponding to the magnitudes of the individual angular momenta.

are quantum numbers corresponding to the magnitudes of the individual angular momenta.

Total angular momentum of an electron in the atom

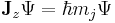

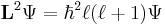

Due to the spin-orbit interaction in the atom, the orbital angular momentum no longer commutes with the Hamiltonian, nor does the spin. These therefore change over time. However the total angular momentum J does commute with the Hamiltonian and so is constant. J is defined through

L being the orbital angular momentum and S the spin. The total angular momentum satisfies the same commutation relations as angular momentum, namely

from which follows

where Ji stand for Jx, Jy, and Jz.

The quantum numbers describing the system, which are constant over time, are now j and mj, defined through the action of J on the wavefunction

So that j is related to the norm of the total angular momentum and mj to its projection along a specified axis.

As with any angular momentum in quantum mechanics, the projection of J along other axes cannot be co-defined with Jz, because they do not commute.

Relation between new and old quantum numbers

j and mj, together with the parity of the quantum state, replace the three quantum numbers ℓ, mℓ and ms (the projection of the spin along the specified axis). The former quantum numbers can be related to the latter.

Furthermore, the eigenvectors of j, mj and parity, which are also eigenvectors of the Hamiltonian, are linear combinations of the eigenvectors of ℓ, mℓ and ms.

List of angular momentum quantum numbers

- Intrinsic (or spin) angular momentum quantum number, or simply spin quantum number

- orbital angular momentum quantum number (the subject of this article)

- magnetic quantum number, related to the orbital momentum quantum number

- total angular momentum quantum number

History

The azimuthal quantum number was carried over from the Bohr model of the atom, and was posited by Arnold Sommerfeld[1]. The Bohr model was derived from spectroscopic analysis of the atom in combination with the Rutherford atomic model. The lowest quantum level was found to have an angular momentum of zero. To simplify the mathematics, orbits were considered as oscillating charges in one dimension and so described as "pendulum" orbits. In three-dimensions the orbit becomes spherical without any nodes crossing the nucleus, similar to a skipping rope that oscillates in one large circle.

See also

- Angular momentum operator

- Basic quantum mechanics

- Particle in a spherically symmetric potential

- Quantum number

References

- ^ Eisberg, Robert (1974). Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei and Particles. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 114-117. ISBN 978-0471234647.

![[J_i, J_j ] = i \hbar \epsilon_{ijk} J_k](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/9c806fccd8d3a97bd8f4376bc9d41efa.png)

![\left[J_i, J^2 \right] = 0](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7f0a85c80dc802597f9d3fa1b0c3b22b.png)